A research team of Japanese scientists and Filipino biologists from the UPLB Museum of Natural History continued its efforts to survey zoonotic diseases from bats, braving the aftermath of Typhoon Paeng (Nalgae) which recently crossed southern Luzon in the Philippines and flooded several areas of Laguna province.

From 30 October to 2 November 2022, the research team spent the long weekend in the immediately accessible forest areas of the University of the Philippines Laguna Quezon Land Grant (UPLQLG) in Real, Quezon, collecting fruit and insect-eating bats. The team’s activities slightly endured intermittent hard rains coming from the outer cloud bands of Typhoon Paeng which was exiting the Philippines.

According to Associate Professor and MNH curator Phillip Alviola, a bat biologist and zoonoses researcher, the group was fortunate to resume its survey activities this year after a two-year hiatus forced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The last time our group conducted a survey was in Biak-na-Bato National Park, Bulacan in early 2020. It was concluded a few weeks before the Philippine government declared the health emergency lockdown,” Alviola said.

The now-relaxed government guidelines have given the team increased mobility and more informed approaches in doing collection activities which have been dissuaded during the past two years by local, national and international government protocols. Currently, the group’s research work is focused on bat parasites and viruses, and the analysis of the risk of infectious diseases from bats which have potential to affect humans and other animals.

According to Dr. Tsutomu Omatsu, leader of the Japanese contingent and researcher at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology-based Center for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention Research, bats are an immense source of viruses which may be detrimental to human health but interestingly, do not make their hosts (bats) ill.

“It is really a mystery in the study of viruses, and solving this puzzle has become more urgent in order to understand pandemics such as the COVID-19,” Omatsu relayed. Dr. Omatsu is joined during the fieldwork by Dr. Hironori Bando of Asahikawa Medical University and Dr. Kentaro Kato of Tohoku University, who is accompanied by his two research students, Nina Watanabe and Lin Xu.

Meanwhile, the MNH team is composed of Prof. Emeritus and curator Joseph Masangkay and his veterinary medicine student Allen John Manalad, Associate Professor and curator Phillip Alviola, researcher Cristian Lucañas, field technicians Edison Cosico and Joel Sarmiento, and extension specialist Florante Cruz.

Philippine bat diversity a potential source of diseases

The exceptional diversity and high level of endemism of bats in the Philippines make the country an excellent location for studying bat-borne diseases. A memorable case was in 2014 when a henipavirus infection likely transmitted to horses from fruit bats caused severe illness and deaths in horses and humans in a town in Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao. Surveillance was quickly employed to investigate the risks and control the spread of the zoonotic infection. Rapid scientific response was done by several health and academic agencies from the Philippines, USA, Australia and Japan.

“But of course, we do not want that scenario again,” Alviola stated, additionally saying that “what we want to achieve now is an active surveillance scheme using prediction models on when and where possible novel diseases may emerge.”

According to Alviola, it is important to carefully study the potentials and risks, both in terms of biodiversity conservation and novel diseases, of bats. For instance, endangered mega bats, which are protected by Philippine laws, has a distribution range encompassing a large part of the country.

“Their ability to fly across seas and traverse islands makes them perfect candidates as transmission agents,” he said. “But while studying their pathogenic loads is equally important, these species should be conserved at the same time specially that direct human disturbances may ecologically put them at greater risk,” the expert added.

The group’s research work currently support steps advocated by the World Health Organization’s Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens. Associate Professor Alviola, a member of the said advisory group, said that bat virus surveillance activities being done in the Philippines will help health institutions, locally and internationally, prepare for new emerging diseases.

“The museum’s ongoing collaboration with Japanese counterparts will enable us to detect novel diseases with genomic surveillance achieved through inter-country scientific partnerships,” he said.

Mix of local expertise and high-end science

Alviola shared that the collaboration of the museum with Japanese institutions has come a long way since its humble beginnings more than a decade ago. “We do acknowledge that this area of virology in the country is still at its infancy, but it is also good to know that there are pockets of scientific research in this area being done in the Philippines,” he said.

Although the Philippines lack the expensive instruments and high-end laboratories, Filipinos scientists have really excelled in understanding the ecology and behavior of Philippine bats. “The collaborations we have had with our Japanese colleagues have benefitted both countries, specially that our local expertise have been tapped for inter-country surveillance activities,” he added.

Research activities done at UP’s Land Grant

Nearly a hundred specimens represented by six species of insectivore and frugivore bats were captured using regular mist nets, V-nets, and sky nets during the four-day collection period at the UP LQLG. The land grant is a 5,729 ha forestland at the foot of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range endowed to the university in 1930.

The different methods enabled the team to capture various bat species which have very particular behavior. “Some bats like to fly close to the ground, so regular nets will suffice; but there are species which fly high in open spaces, thus we need to use sky nets that rise up to 30 feet above the ground,” Alviola explained.

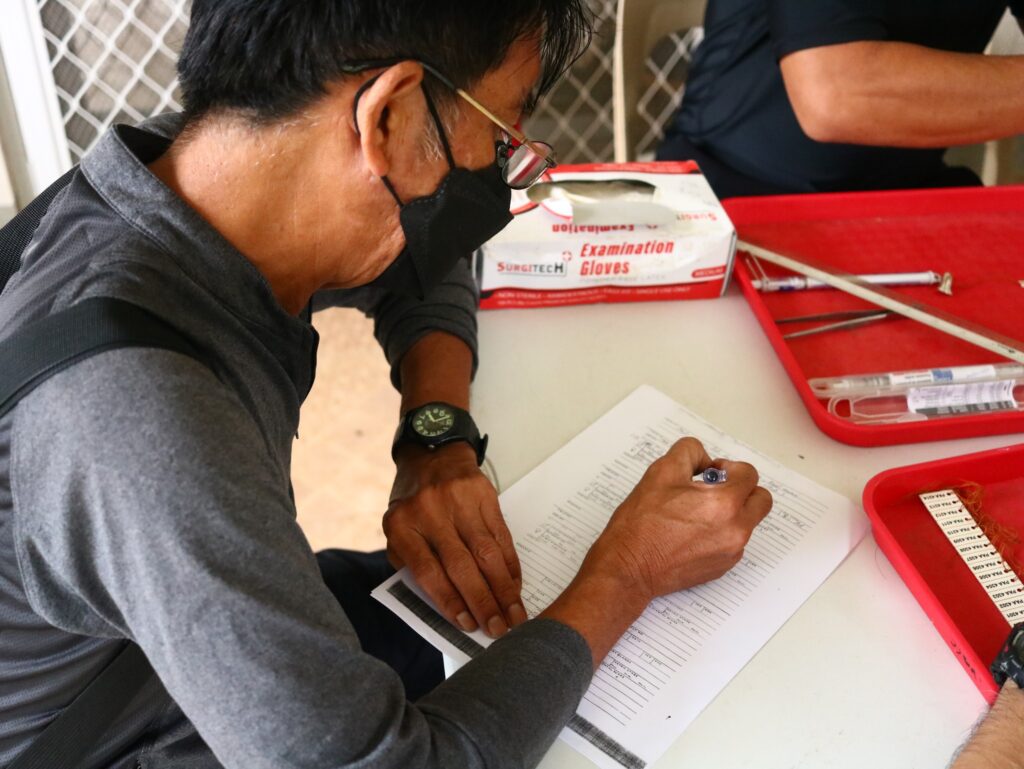

The bats were then systematically processed by members of the research group. Alviola’s team determined morphological data and collect bat ectoparasites while the Japanese scientists concentrated on the clinical preparation of sources of data.

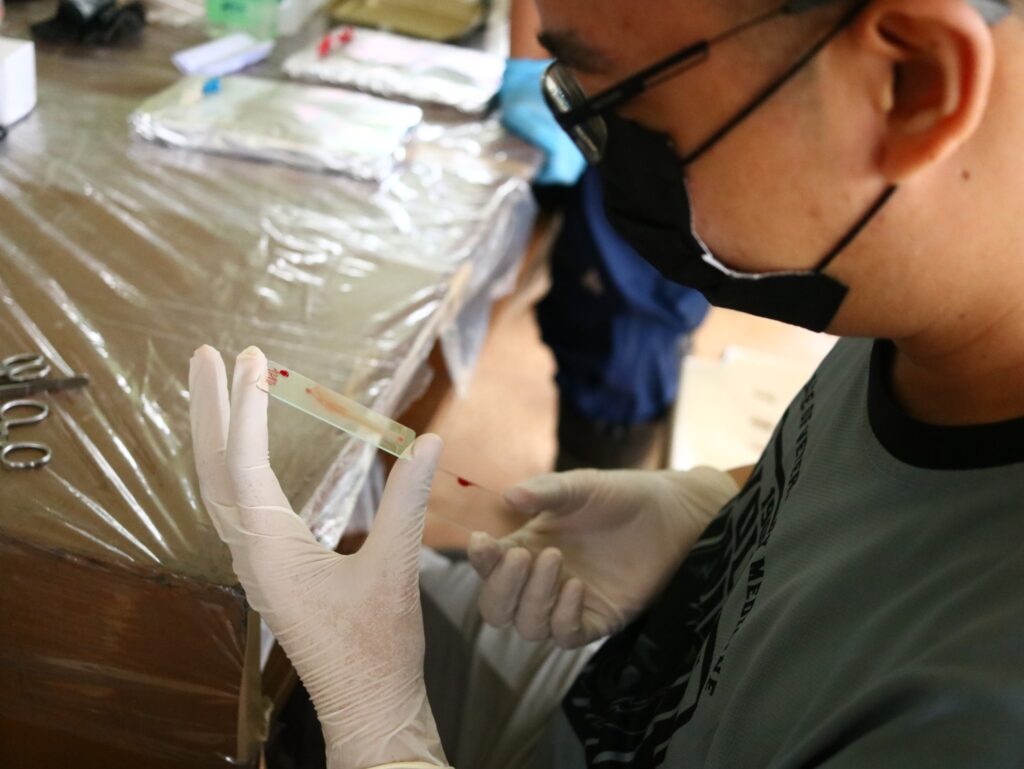

“I draw blood from the bat after it has been given anesthesia, and the blood will be studied for the infection of viruses,” Dr. Omatsu shared. Dr. Omatsu is currently the leader of the project “Development of a Simulation Model for Prediction of the Next Outbreak of Bat-derived Coronavirus Infection in Humans” which he is co-implementing with Alviola and Associate Professor Ngan Pham of Vietnam National University of Agriculture.

On the other hand, collaborators Dr. Kato and Dr. Bando processed parts such as the bat’s gut, liver, spleen, and others which have been determined as possible sources of viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and other pathogens. Veterinary student Allen John Manalad made blood smears and collected bat hair and other tissues and organs as well. As required in the permits issued to the group, the bat carcasses have been stored at the UPLB Museum of Natural History as voucher specimens.

“All of tissue samples will be brought to Japan for high-throughput genomic analysis, where it is easily doable,” Dr. Omatsu shared. “All data on the bat’s morphology and ecology are integrated to reveal important information which we hope to clarify viral mysteries, including that of the origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” he added.

(This article, written by Florante Cruz, was first published in the UPLB Museum of National History Website on November 21, 2022)