While recent news of giant clams (Tridacna gigas) being harvested in the disputed Scarborough Shoal drew massive outrage online, it was only the latest low point in the dark history of wildlife exploitation in the region. A poignant series of cases also happened here in 2013 and 2014, this time involving pangolins or “scaly anteaters,” which have been described as the most trafficked animals in the world.

All eight species of pangolins have been declared to be at least threatened globally. The Philippine pangolin (Manis culionensis), however, has been named critically endangered. It was no surprise then that the nation recoiled in horror in 2013 when a Chinese vessel stranded in the Tubbataha marine national park was found with over 3,000 frozen pangolins on board. Barely a year later, Palawan officials confiscated even more of these from two residential buildings and a tricycle in Puerto Princesa City.

While everyone feared that Palawan-endemic Philippine pangolins were the ones involved, this proved difficult to confirm visually. As pangolins are hunted primarily for their scales, which are made of keratin (the same as that found in human hair and nails) and meat, they are typically skinned after being smoked out, bludgeoned to death, and boiled beyond recognition. For justice to be served, what was needed here was a scientifically credible system to ascertain the exact pangolin species found in these shipments.

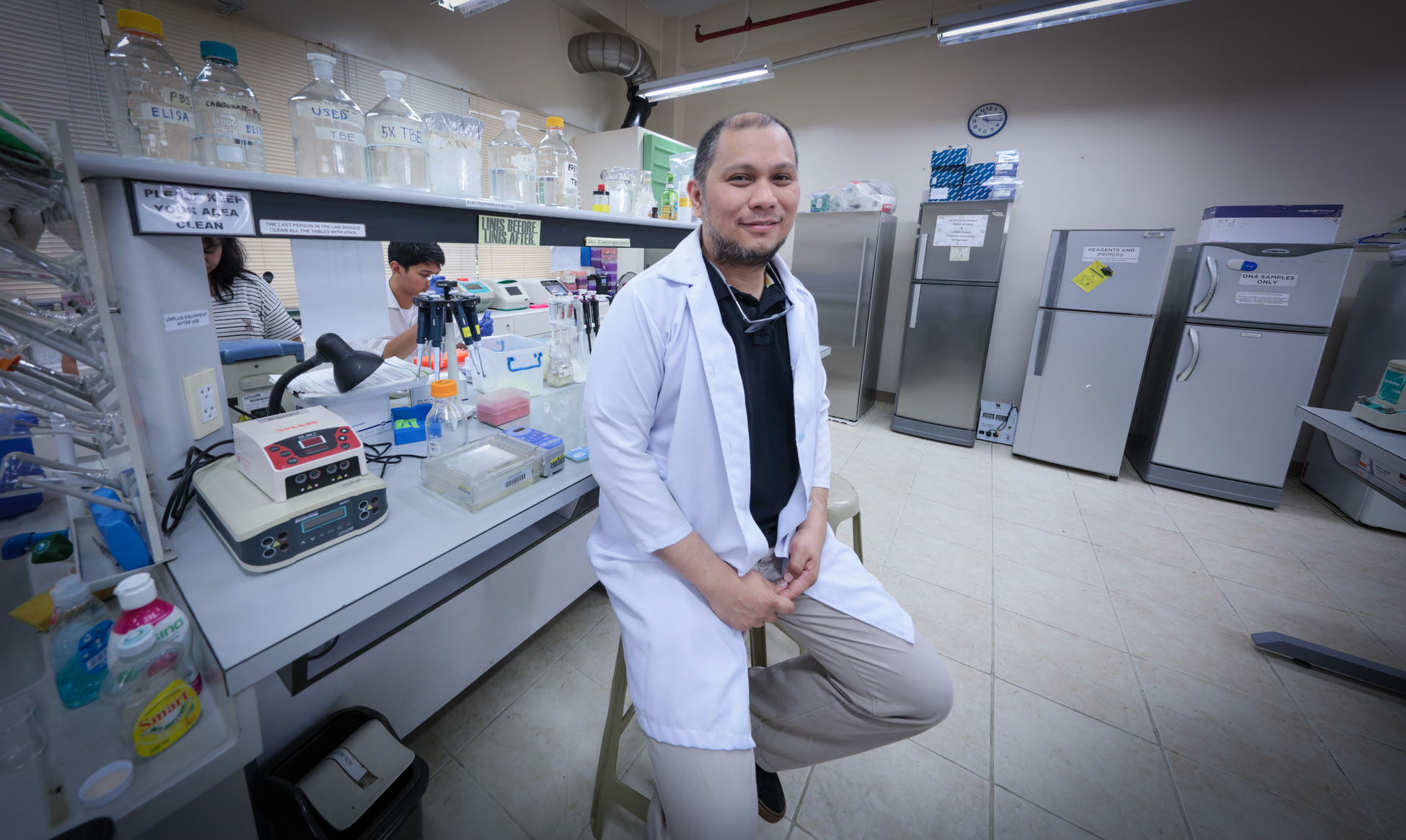

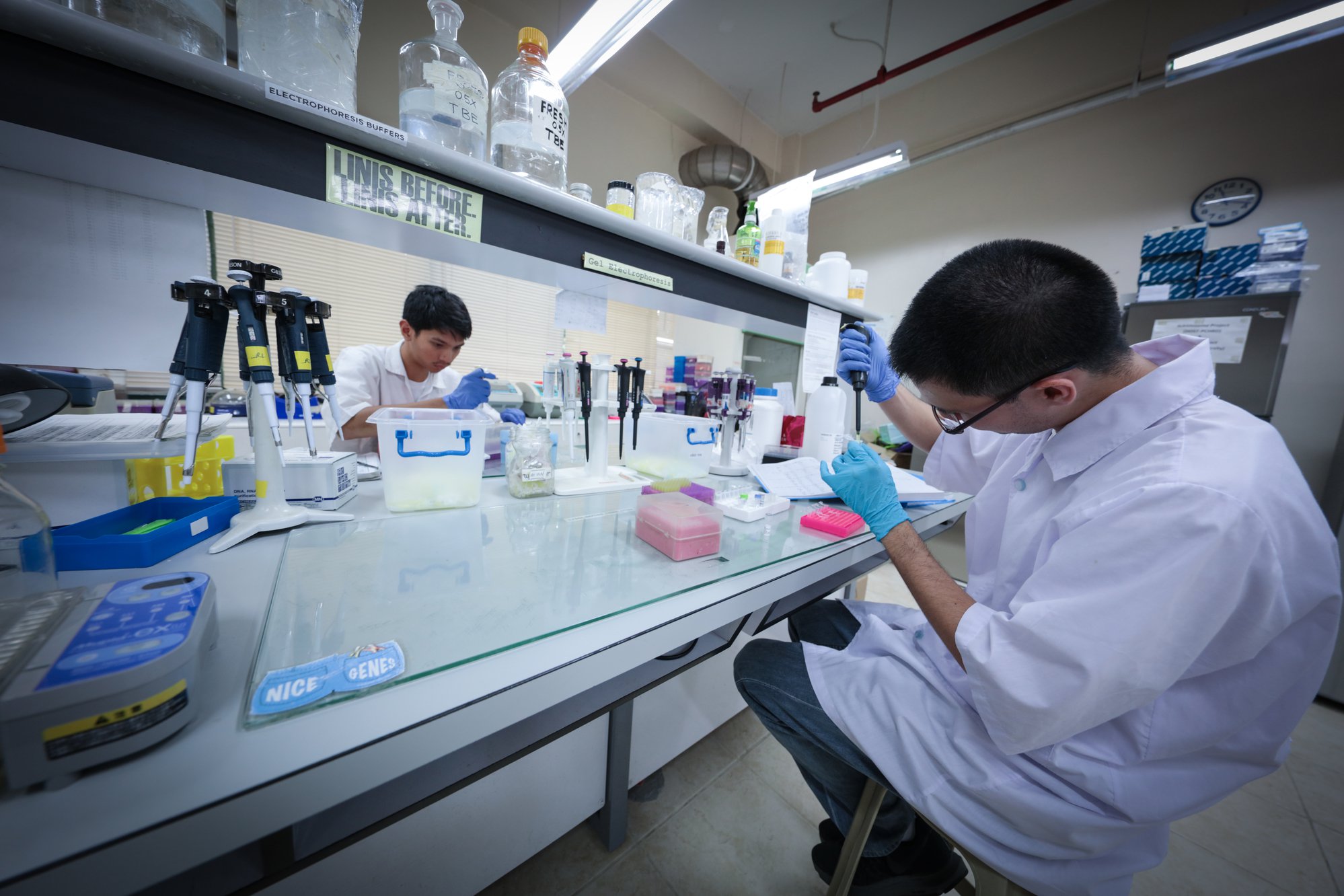

Luckily, a team from the University of the Philippines Institute of Biology led by Dr. Ian Kendrich Fontanilla, Mr. Adrian Luczon and the late Dr. Perry Ong had been working to perfect such a system. The geneticists and the conservation biologist joined forces with fellow experts to pioneer a method called DNA barcoding.

DNA barcoding uses the molecular fingerprint of DNA found in even processed remains to accurately determine the specific species. This is done by reading selected genes like product barcodes against a database of samples collected, to aid both science and law enforcement. Together with a close-knit group of institutions, Fontanilla is working to help this database include all endemic species in the country and be a frontline tool against illegal wildlife exploitation.

Genes and Shakespeare

While the country is equipped with legislation to protect local biodiversity in the form of Republic Act No. 9417, or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, Fontanilla explained how difficult it is to uphold this law. As in the case of the Palawan pangolins, agents of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) used to rely purely on morphology, or a specimen’s appearance, to determine species in their custody. This, as we have seen, can prove unreliable.

It was in 2008 that Fontanilla, together with other geneticists, Dr. Jonas Quilang and Dr. Zubaida Basiao, joined forces with Ong, at that time the director of the Institute of Biology and a prominent wildlife biologist, to craft what would become their public database of DNA barcodes. A few years later, Ong approached the DENR with a proposal. “Why don’t we help each other?” Fontanilla recalled Ong proposing. “We can help you identify species at the molecular level, and you can provide us with samples.” This offer officially began the partnership between the two institutions that persists to this day.

Being more focused on the molecular side as head of the Institute’s DNA Barcoding Laboratory and now the director of the Philippine Genome Center’s (PGC) Biodiversity program, Fontanilla explained that not just any gene can be used as a barcode. “You can think of the DNA of all species like the pages of Shakespeare’s books,” he said. “Now of course we can’t identify them without their titles so now we have to pick a page from each book.”

This “page” or specific gene in our DNA is one that facilitates easy identification. “It’s like when you open page 5 and read Romeo’s words to Juliet, and then you know what work it is.” The copies of any collected gene are compared to the current contents of the database to find the most accurate match. “That’s what we do in DNA barcoding, we find a gene that can discriminate like that.”

Powerhouse

For animals, Fontanilla and his team use the gene Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I or CO1. Unlike most genes we are familiar with that are found in the cell’s nucleus, CO1 is found in mitochondria. “The mitochondria are what produce ATP (which produces energy for many cell processes); so the mutation rate there is very high,” he said. This high rate of mutation across time is what creates the variability that allows us to discriminate between even closely related species.

With genes like CO1 playing the role of the perfect pages, Fontanilla and Ong joined their partners in filling up their database. This involved going out into the field to extract both tissue samples for DNA and measurements from enough animals. “As much as possible we try not to kill them,” Fontanilla said. Using the case of local bats, he illustrated the challenge of catching and releasing them unharmed for this purpose.

“We had mist nets for us to catch them,” he recounted. And when they had one trapped, the group had to be very careful not to damage their wings during the extraction process. After taking its measurements (which also go into the database), the bats are carefully released by allowing them to grab onto a tree. “Ideally we get more than 5 specimens per locale,” Fontanilla said. “Because if you just base your data on one individual, what is the variability of that population for that specific gene? We need population data.”

Fortunately, the mission to create a good database is now one they share with key allies. Together with the University of the Philippines Diliman and the Philippine Genome Center, universities like De La Salle University and the University of Santo Tomas, among others, have since joined them. Government agencies like the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), the Department of Agriculture (DA) and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) are now also prominent members of this barcoding effort.

Always Remembered

When recounting the group’s successes so far, Fontanilla fondly remembers Ong’s contributions to the barcoding cause, which lasted up to his passing last March. “It was Doc Perry who pushed for this,” he said. “Because being in the academe, we could not do this all on our own. We could not stay in our ivory towers and do research that did not have societal impact. The government is paying us to make that impact.”

This spirit of reaching out was exemplified fully by the late College of Science dean. His establishment of their mutually beneficial partnership with the DENR paved the way for the growth of both their allies and the DNA barcoding database itself.

The publication of a paper in 2016 on the pangolin case above was the first to document the effectivity of these partnerships. Using the power of DNA barcoding, Luczon and Fontanilla of the DNA Barcoding Laboratory and Ong’s Biodiversity Research Laboratory managed to determine that the 73 specimens confiscated in Puerto Princesa were indeed Philippine pangolins coming from a single locality. The 12 samples they analyzed from the Tubbataha case, on the other hand, were from the closely related Malayan pangolin (M. javanica), another critically endangered variety from Southeast Asia.

While Ong is no longer around to see the future growth of the barcoding database, Fontanilla said that his collaborative spirit continues to inspire him and his colleagues.

“When Dr. Perry passed on, all of our partners came together in one place to pay their respects. A sad but necessary result of that is we all met and agreed to finish the projects that we had planned together. And we do plan on finishing them all.”

To access the Barcode of Life Data System, visit: http://www.boldsystems.org.

(This was originally posted in the University of the Philippines website on June 4, 2019.)